Leo Luster

Straight to the filmWE FELT AT EASE IN VIENNA

UNTIL ANTISEMITISM INCREASED

Leo Luster

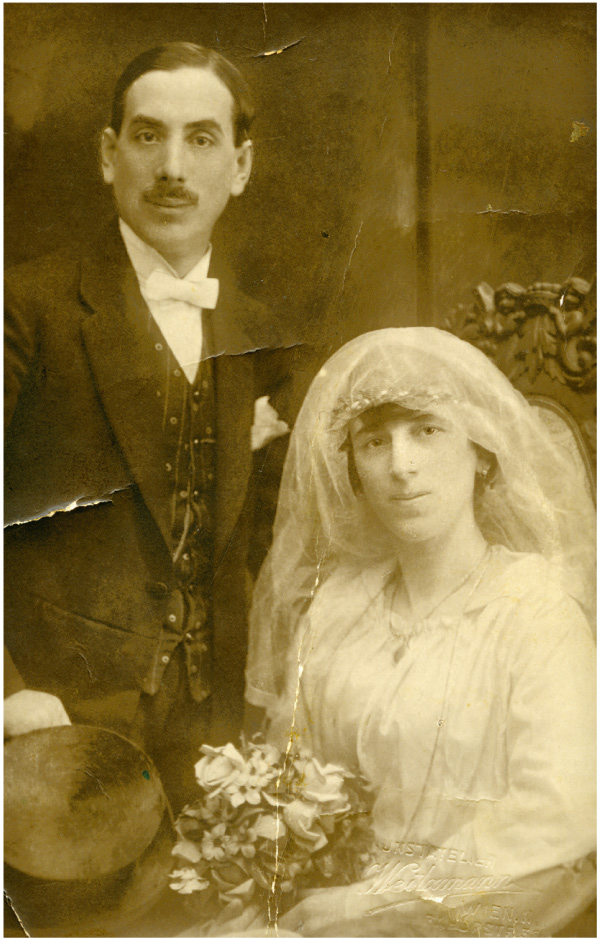

My parents met through a matchmaker. They were married in Vienna in 1920 in the Polish temple at Leopoldgasse 29. We lived at Schreygasse 12 in the 2nd district. Two thirds of the people in our building were Jewish. In our apartment there was a large room, a small room where my sister and I slept, and a kitchen.

My parents always went to temple on Fridays for Shabbat services. After services we often gathered at my Uncle Benjamin’s, since he had a large apartment. There the whole mispocha [Yiddish: family] was together. We felt at ease in Vienna until antisemitism increased. In 1936 a lot of our friends from our building immigrated to Palestine. I think my parents would have also immigrated to Palestine, since my mother and father were not Austrian patriots.

My sister Helene was born in 1921. I was born in 1927. Helli looked after me a lot. We had a good relationship. We could already very clearly sense the antisemitism back then. We played soccer on the street and the Christian children often beat us up. We would never walk to school alone, always in groups, so that they couldn’t attack us.

For the first four grades I went to the Talmud Torah School at Malzgasse 16, a very religious school. For the next four years I was at a secondary school on Vereinsgasse, and then I was at the High School on Sperlgasse. The teachers at the Christian schools always discriminated against us Jewish children. We couldn’t do anything about it.

In 1941, once I finished the eighth grade on Sperlgasse, they turned the school into a deportation center. During the time in which we Jewish children weren’t allowed to go to school anymore, we went to the JUAL School and learned primarily about Zionism. I went to that school until our deportation.

On November 10th, 1938, pogroms against Jewish stores and synagogues took place, and Jews all over the country were arrested. The Nazis called these anti-Jewish pogroms “Kristallnacht”. My father was arrested and detained. When my father was released he was pretty beaten up. They told him he couldn’t tell anyone about his experience. They had beaten and tortured the people in the prison.

On September 24th, 1942, we were taken from the collection point at Sperlgasse 2a, led to open trucks by people insulting us, and then taken to the Aspang train station. They even threw tomatoes at us, and the Viennese yelled, ‘Jews get out!’ I was devastated about how people could be so full of hatred.

Because my father worked for the Jewish Community we weren’t deported to Nazi-occupied Poland like other Jews from Vienna – yet – , but to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. We were on the train for two days with over a thousand people. Then we arrived in Bauschowitz [Bohušovice. Today: Czech Republic]. We had to walk for several kilometres to the ghetto. I was in Theresienstadt until September 1944, when we were deported in cattle cars to Auschwitz. When we arrived, we didn’t understand what was happening there, and I lost sight of my father. A few hours later I saw the crematorium. We asked the other prisoners where they were bringing the people who were led away from the platform. Someone said to me, ‘do you see the chimney and the smoke there?’

My friends and I were lucky: we stayed alive and the Nazis ordered that we repair broken train cars. In one of these train we found pages from a newspaper and read that the Russians were outside Warsaw. A few days later, the guards gave each of us half a piece of bread, a can of black pudding, a bit of margarine and jam, and made us march for days. That was a death march.

The guards shot whoever stayed back. We weren’t given anything else to eat. After three days we reached Blechhammer [Blachownia Śląska, Poland], an Auschwitz satellite camp. My friends and I were brought to a barrack. In the morning we were to get up and report to roll call. We hid in the barracks, since people who couldn’t walk were shot. As soon as the SS men noticed that a lot of people were hiding, they began setting the barracks on fire. Those who ran outside were shot like rabbits. Our barrack also began to burn, but we had found bottled soda water in the barracks, which we poured onto the fire and that’s how we survived. They shot people the entire day and then they were gone. I found some bread and I took as much for my friend and me as I could carry. We walked along a street that went through the woods. All of a sudden we heard the sound of motors. We walked out onto the street with our hands up. The first car stopped. A soldier got out. I saw that he was also scared, so I said “Yid, ya. Yid, yid.” (Jew, I. Jew, Jew) He looked at us and said, “ya tozhe yid” (I am also a Jew). We told him that there was a camp. Then his company occupied and took over the camp.

The war was over on May 8th, 1945. The Russians said, ‘Go wherever you want. You are free!’ By chance we learned there were still people in Theresienstadt. I hadn’t anticipated that. Typhus had broken out in the camp. There I met a friend of my fathers. He said to me, ‘Have you already been to your mother’s? I saw her, she is here!’ I don’t know if you can imagine how that was for me. I found my mother in an attic. The first question she asked me was, ‘where is Dad?’ I couldn’t say anything and she only said, ‘God has bestowed this upon me, you being alive’.

We got the chance to travel to Bavaria. That’s how we arrived to the Displaced Persons camp in Deggendorf. We had a very nice time in Deggendorf. We stayed there for four years. I lived with my mother in a room in the barracks. The State of Israel was proclaimed in 1948. In late 1949 my mother and I left for Marseille. From there we traveled by ship to Haifa. That was the first time either of us had ever seen a ship with an Israeli flag. That was a terrific journey! On the last night we danced; everyone wanted to see Haifa as it appeared. At around five in the morning we saw the lights on the coast. That was a great moment – it was incredible!

I lived with my mother. But I desperately wanted to go to my sister. So with my pocket money I took a shared taxi from the camp to Hadera and looked for my sister’s address. Our first encounter is difficult to describe. I recognized her immediately from the photos she sent us in Deggendorf after the war. It was very moving.

“The past is another country”

Leo Luster grew up in Vienna during the interwar period. But in 1938, at the age of 11, Leo and his family were forced first to witness the “Anschluss” – the annexation of Austria to the German Reich – and then several months later the infamous “Kristallnacht” pogrom. His father lost his job and the family their apartment. In September 1942, Leo and his parents were deported from Vienna to the Theresienstadt ghetto. After two years, he and his father were deported to Auschwitz while his mother stayed behind in Theresienstadt. In January 1945 Leo was sent on a death march, but was able to survive nonetheless. He was liberated by the Soviet Army and afterward was able to find his mother again. In 1949 they emigrated to Israel, where Leo has been living until today.