GOD SPOKE TO ME TODAY

Kurt Rosenkranz

My father, Michael Rosenkranz, was born in 1897. At the start of the First World War, he set out on his own for Vienna, with only tallit and tefillin in has pack. In Vienna my father learned to cut for shoes in the Eterna factory and became a preeminent expert. My mother went to the commercial academy in Vienna and became a secretary at the Phönix insurance agency. My parents met in Vienna and were married in 1923. My brother, Herbert, was born in 1924. I was born in 1927. We were kosher, celebrated all the Jewish holidays, and my father went to the Kaschl temple every Shabbat.

My father opened a shoe manufactory on Kleeblattgasse in the 1st district, and my mother occasionally worked for him. During the 1934 financial crisis, my father had to liquidate his shoe factory. That’s why we began living with my grandparents in 1934. Together with some friends, my parents founded the Russian-Polish Jewish Association in Vienna, since they and many Russian and Polish Jews weren’t able to successfully integrate into the Jewish community by 1938.

My paternal grandfather was called Dov Rosenkranz. He lived with his family in Poland, in the city of Radom. He was the head of the temple and very respected. In orthodox Judaism it is the highest duty to learn throughout life, and my grandfather was a learner for his whole life.

My grandmother was not only the mother of seven children, she was also the one who earned the money. My grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins only spoke Yiddish and only attended Jewish schools.

I went to the first grade of middle school, and several days before the German invasion, in March 1938, I was still playing soccer in the street with my non-Jewish classmates. On Friday evening Hitler marched in. We were at my grandparent’s place, it was Shabbat. All of a sudden we heard on the radio, ‘God save Austria!’ Those were Schuschnigg’s last words, and my mother wept bitterly because she knew what was coming. It had no effect on me. But on Saturday morning, the looting began in Vienna.

On Monday I went to school and our class teacher arrived to the classroom wearing an SA uniform and greeted us with “Heil Hitler.” His first sentence was, “Jews out!” We had to sit in the last row of benches in the class. I was immediately eliminated from the soccer team. No child dared to speak with us Jewish children. We were lepers.

We barely had the courage to leave the house, since the Hitler Youth, who were out in the streets, were not only looting but also beating up Jews. My parents looked for ways we could possibly get away. My father almost didn’t go out on the street anymore because the men were being taken from the streets to be put in jail and deported to the concentration camp. My mother came home one day and said there was the possibility of emigrating to Riga.

Sine there was no Latvian embassy in Vienna, my mother wrote to the Latvian Embassy in Berlin. A reply came in the mail: Yes, you may have a tourist visa, but you must pick it up in Berlin. In the fall of 1938 we packed only the most essential items. The embassy wrote to us that we had to look like tourists to avoid any problems at the border. We said good-bye to my grandparents. My grandfather died in 1942 in Vienna of natural causes. My late grandmother Rifka was deported in 1942 to Teresienstadt and then murdered in Treblinka. We were in Berlin for several hours, picked up our visa from the embassy, and took a train to Stettin [Today Szczecin, Poland]. In the port of Stettin, we were inspected by SA people. Their last words before we got on the ship were: “Dirty Jews, don’t come back here again. If you do, you can’t image what’ll happen to you.”

After five days we arrived in Riga and were greeted by the Riga Jewish community. We were given two rooms at the home of a Jewish family. A wonderful time began for me. I could play soccer again and had friends. We could move freely. In [1939] Stalin and Hitler signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Russians occupied Riga.

My father was given a work permit and became the vice director of a shoe factory, since after all he was an expert. One day our teacher came with questionnaires for the children who wanted to be pioneers. The children who didn’t join were treated like lepers by the other pupils. I even ran home with a red kerchief around my neck. My bar mitzvah was during this time and I was supposed to be accepted into the circle of Jewish youth who’ve reached religious maturity. But I was a communist! My parents lost all contact with me because I was such an enthusiastic pioneer. I ate at home and was at home for Shabbat, but I didn’t go to temple. I lived in another world. My brother convinced me to become a bar mitzvah. I did, however, have one condition: I will become a bar mitzvah with the tallit and the prayer shawl, but also with my red pioneer neckerchief!

Then came the 22nd of June, 1941 – the outbreak of war! At around four in the morning there was a knock at the door. A Red Army soldier was standing outside. He said we were to pack up and be done in five minutes. That came to us as a total surprise. Since we were German citizens and considered potential spies, we were imprisoned. It didn’t matter that we were Jews. We were interned in the French Lyceum in Riga, experienced three German air raids and, after several days, were thrown onto freight cars. There were cots in the freight cars, and there was bread and water. This is how we rode to Siberia, to Novosibirsk. In Novosibirsk we were brought on foot like felons under strictest watch to a relatively small internment camp. No one was allowed to work. The living conditions got worse and the aggression grew.

After one year we were brought on cattle cars to Karaganda in Kazakhstan. After a long march on foot, we had to carry our packs, we slept outside in a camp with barbed wire. The next day we marched 40 kilometers [approx. 25 miles] through the steppes. In the evening we arrived and found ourselves in the central camp for German prisoners of war. That was in 1942. The German prisoners were luckily separated from us. I became a herder and had to watch pigs, sheep and cows by wind and storm, by snow and ice. Since my father had dysentery and typhus, he lay in the infirmary and we weren’t allowed to visit him. One day I thought I heard God. He said, “you must go to your father.” I fought my way to my father. He was ready to die. He had given up, since had no more contact to family. I threw myself on him and shook him, “Papa, Papa!” He looked at me and mobilized what little strength he had. That’s how I saved his life.

Then came the year 1944. More and more people died. One day a doctor came. This doctor first of all wrote the entire camp a sick note. The commander was in a rage. But suddenly there was milk, sugar, and eggs for the children, and much better food for everyone. Life began again. After the war we hoped to be set free. We were told that we still had to gather in the harvest, and then we’d be allowed to go home. The harvest was inside; we didn’t go home. At the end of December 1946, in the middle of a snowstorm, trucks came to pick us up. We were riding in cattle cars, but we were free. In March 1947 we arrived to the Matzleinsdorfer freight station in Vienna. We went to the homeless shelter on Meldemann Strasse. The first night in our own beds! We hadn’t had that for years! After eight months we were given an apartment with several rooms at Taborstrasse 24a. My father started again with a small shoe factory.

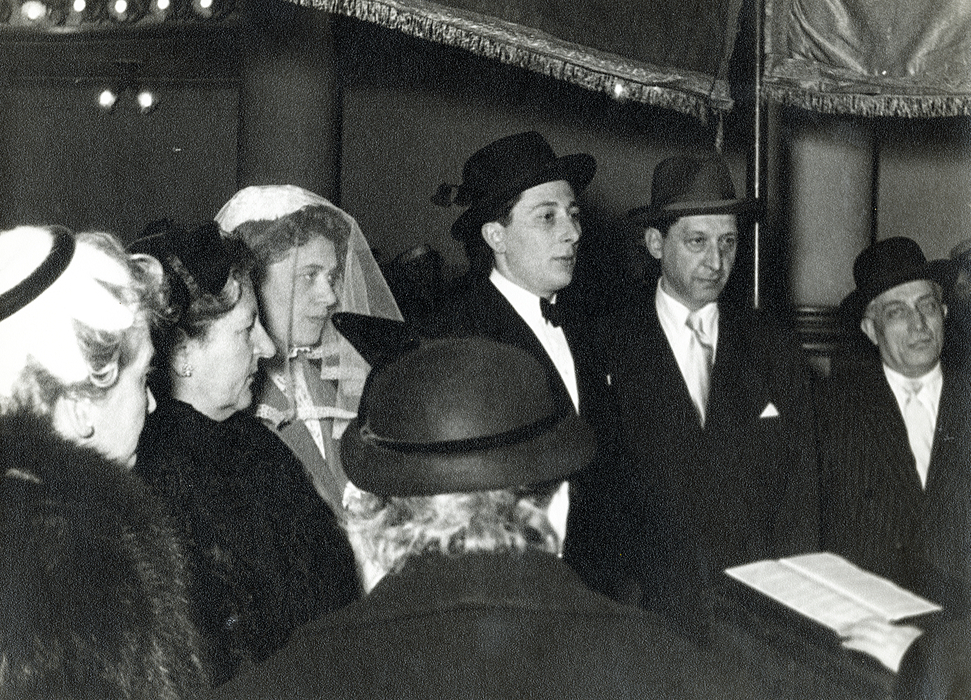

I met my wife, Erika, at the Hakoah. She and her family had survived the Holocaust in Monaco, France, Belgium, and Switzerland. And so we were married on January 5th, 1956 in the synagogue on Seitenstettengasse in Vienna’s 1st district. We were the first couple after the war to have both pairs of parents standing beneath the chuppah. In 1959 our daughter, Lydia, was born.

One day the president of the Jewish community came to me and said, “Kurt, a delegation from Germany is coming. Tell them a little something about the temple.” After the war I asked myself: why did you survive? And as I was standing before the altar in the temple and talking, it came to me like a bolt from God. He spoke, “Kurt, I let you survive for this.” I still get cold when I think about it. That was the beginning of my institute. On September 15th, 1989, I opened the Jewish Institute for Adult Education at Praterstern 1. This is the only institute in the world that is mainly there for non-Jews. I’m proud of it. Several years ago I received the Karl Renner Prize for my work, the highest cultural award in Austria.