Max Uri

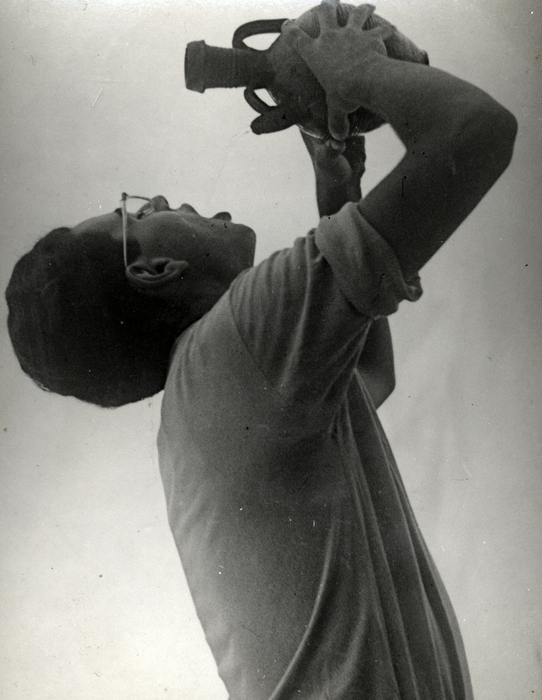

Straight to the filmWHEN SHE SAW ME, FRITZI DROPPED THE BOTTLE

Max Uri

Max Uris Familie väterlicherseits. Von links stehen Alexander Uri, der in Israel streng orthodox wurde, Mina Uri, Rosa mit Ehemann, Frieda Zwick, Jakob Uri, Herman Uri, Isak Uri. Sitzend: David Uri, Osias Uri, der Vater von

Max, Großmutter Regina, Großvater Lazar, Moses Zwick, Helene Uri, die Ehefrau von Herman Uri. Die Kinder: Max Schwestern Edith und Cilli, Paul Zwick und Fanny Zwick.

My paternal grandfather was called Lazar – Jewish name Luzer – Uri. He was born in 1865 in Galicia and worked as a merchant. In 1882 he married my grandmother Regina – Jewish name Rivke – whom they called Rifka. Both my grandfather and grandmother came from strictly Orthodox families. My grandfather saw that he couldn’t be as successful in Galicia as he could in Vienna, so in 1893 the family relocated to Vienna.

Grandfather was a tall, good-looking, strictly Orthodox man with a beard and payot that he wore behind his ears. Grandmother kept a kosher household, wore a sheitl, and kept her hair cut short beneath the sheitl. Starting in 1894, grandfather owned a clothing manufactory called Lazar Uri on Judengasse at the corner of Hoher Markt. He received large orders from the army and became the high supplier for uniforms for the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

In 1910 my grandfather had handed over the Lazar Uri business to his sons Hermann, Isak, and Jakob and name was changed to Uri Brothers.

Back then, a husband received his wife’s dowry at the wedding. When my aunt Frieda, my father’s oldest sister, got married, her husband disappeared on their wedding night with the dowry. Just imagine the shame for aunt Frieda and the whole Uri family! She needed to find a new husband quickly – and that was Moses Zwick. Moses Zwick, a good-looking snob, agreed on one condition: he will only marry Aunt Frieda if they bring him into the business as co-partner. That’s how Moses Zwick became partners with my father who had worked in my grandfather’s business for the first years, but who was by then self-employed.

Moses Zwick was not good for the business; he only cared about himself, and if he was ever in the shop, he fought with the customers, made stupid jokes, and didn’t get along with the other employees.

I was born in Vienna in 1921. At the time, my parents were living in the 1st district, at Salvatorgasse 10. After primary school I went to high school on Sperlgasse. Most of the children were Jewish. During the High Holidays, on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the whole school was closed, since it wouldn’t have been worthwhile to keep the school open for the few non-Jewish students.

After my fourth year of high school I went to the commercial academy at Karlsplatz, since I was to take over the business someday. It was a large class with about 60 students at the commercial academy. Out of 60 students, about eight were Jewish and the rest were already illegal Nazis. Nonetheless, I got along well with them. I can still remember the German invasion of Austria in March 1938 well. We were living in a good neighborhood, and in the evening we heard on the radio Chancellor Schuschnigg resign. We turned off the light in the living room. Not far from our apartment, on Karl-Lueger-Platz square, the mob raged against the Jews. Shortly thereafter I had to leave the vocational college. My classmates asked me, “Maxl, what will you do now?” I said, “I think I’ll go to Palestine.” Then they said, “Maxl, don’t go away, you’re a great Jew!” And I said, “I’m a great Jew to you, but for the others I’m Jewish swine.”

On November 10th, 1938 I was arrested and detained in the 9th district in a riding school on Pramergasse with around a thousand other Jews, some of whom had been taken from their homes in pajamas or undergarments. Around three in the morning those under 18 and over 60 years of age were allowed to go home. A mob had gathered outside and was waiting for us. A high-ranking police officer was prepared to protect us, but only for as long as it took him to count to ten. I ran, which luckily was easy for me as an athlete.

We struggled to get out of Vienna. After the pogrom night, taxes were imposed on Jews, such as the Reich Flight Tax and the Judenvermögensabgabe [Jewish Property Tax]. Because of this, we had tax debt and our business was also taken from us. Since you needed to be debt-free in order to get a passport, the official at the Gestapo said to my mother, “I’ll give your children passports, but you’ll stay here as a deposit.” My mother still had the money to pay for me to study at the Mikveh Israel agricultural college near Tel Aviv.

My later wife, Fritzi, and I had already met as children. We spent the summer together at a Jewish youth camp in Breitenstein am Semmerring. The following summer my mother was with my brother and me in Abbazia at a summer resort. There I met my wife and her mother at the kosher hotel and from that point forward we started going out together.

And one day my girlfriend, Fritzi, wasn’t there anymore. Back then, in that situation, you couldn’t tell anyone about leaving, not even your closest relatives, because of the risk of being imprisoned.

On the first day at Mikveh Israel the director gave us the day off so that we could visit our relatives living in Palestine. I wanted to visit my uncle David who was living in Tel Aviv. And just as I am walking down the street, I all of a sudden see Fritzi, my girlfriend from Vienna. I still remember it well: she was holding a bottle and when she saw me, she dropped it and it broke. I always say: It was God’s intention that we two should get married.

In December 1941, my wife and I were married in Tel Aviv. My wedding day wasn’t just a happy one, I was also very sad, since I only had uncle David in Tel Aviv.

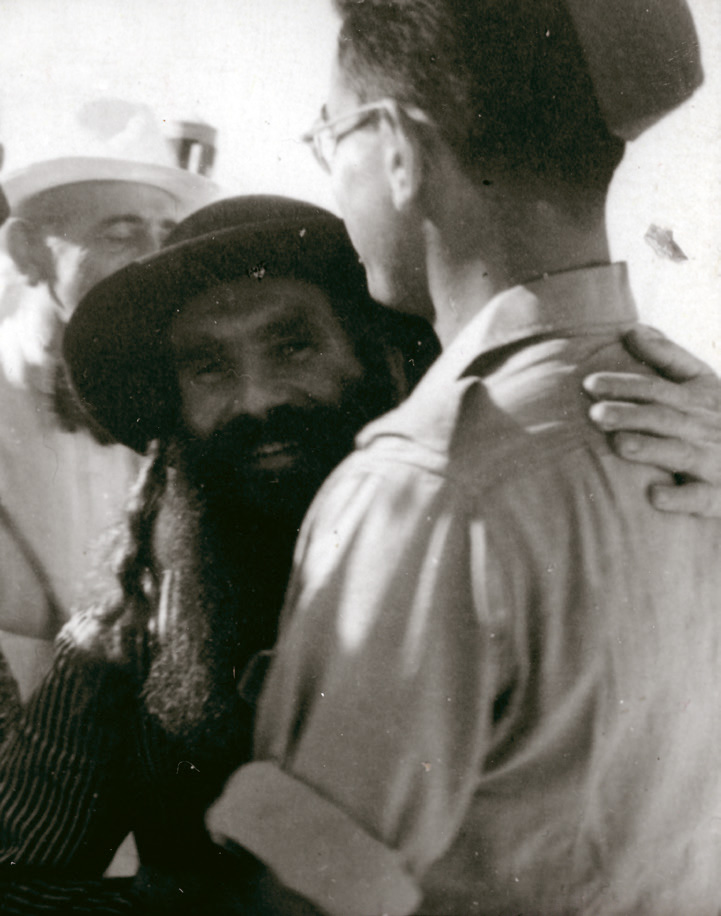

My Uncle Alexander was living in Jerusalem, but he was poor, never had money, and would have had to pay for the bus from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv to come to my wedding, which I didn’t want to ask of him. I thought: I have to send him an invitation, but I will send it so that it will arrive too late and he won’t have to spend the money on a bus. So I brought the invitation to the post office on the morning of the wedding. Of all things, the mail was especially quick that day, so that he got the invitation by the afternoon. He immediately boarded a bus and rode to Tel Aviv.

In the early years at Mikveh Israel, I signed up with the Haganah. I was trained with the Haganah and after two-and-a-half years, just before I finished at the agricultural college, the order suddenly came that we needed to sign up with the military, because the Germans were already in Alexandria and the English knew that we had excellent training from the Haganah. From May 8th, 1941 I was a soldier in the English Army in Palestine.

Just before the birth of my son Ralph in January 1941, I was badly wounded from the faulty operation of a cannon near Akko. After that I was sent to my old unit in Cyprus. At this time, the Jewish Brigade was being formed within the English Army. The Jewish Brigade was made up of around seven to eight thousand people – the infantry, artillery, and so on. In 1944, just before the end of the war, I went to Italy as a bombardier with the Jewish Brigade. In Italy we fought on the front, and then the war was over. We were sent as occupying troops through Germany to Belgium and Holland.

After a long search I got work as a gardener. Because of this trouble with work – otherwise we would have likely stayed in Palestine – we decided to immigrate to America. After the German invasion my mother had tried to get us an entry permit at the American Embassy. We were told that the quota number they gave us back then was no longer valid, so we had to re-register, and that the permit could take one or two years because the displaced persons would be the first to receive entry permits to travel to America. So we decided to go back to Austria first.

We lived in a five-room apartment and brought my parents-in-law to live with us. Uri & Zwick had been looted and run down. Not long after, my father-in-law re-opened his fur business. I worked alongside him, but when we learned that there was nothing standing in the way of our entry to America, we emigrated in 1952 with our by then three children – in December 1949 the twins, Eva and Robert, were born – to America.

After a week in New York, we had the money and flew to Los Angeles. I put half of the money into a business, but my supposed co-partner was a swindler and I lost almost everything. Luckily, a company offered me a job. After eleven years in Los Angeles, in 1963, we had established ourselves in America and were doing well. We had a really nice house with a swimming pool. Our children went to school, and we rent regularly to the synagogue and celebrated all the Jewish holidays. Then my father-in-law asked me to come back to Vienna, because he was old and sick. So we packed up our things and came back to Vienna. Since I hadn’t had any bad experiences in Vienna before the Holocaust and experienced little antisemitism, I went back without reservations and didn’t regret it.

Max Uri – Looking for Frieda, Finding Frieda